Girls choose bad, abusive people, while relegating good, decent ones to the feared “good friend zone”: A misogynistic lie or the cold, difficult fact? Ryuichi Hiroki’s “Wolf Girl and Black Prince” appears to say the latter, beginning with its premise. A naive, socially inefficient high school woman concurs to end up being the “dog” of a handsome, big-headed schoolmate if he pretends to be her partner. That is, she needs to do exactly as he says, doggy tricks consisted of, and in return he will socialize with her in front of her pals– the school’s “cool girl” inner circle. How retrograde is that?

Get the movie here

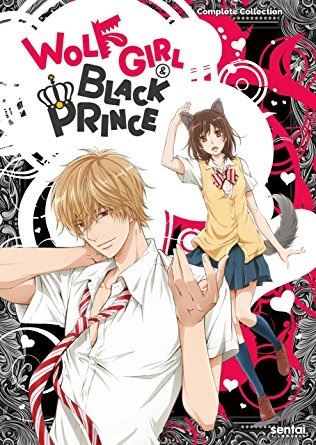

Based upon a very popular girls’ comic by Ayuko Hatta, the film is in fact anything but, though it is honest about the risks and peculiarities of teenage social characteristics, in addition to the unstable mix of pride, loneliness and, yes, decency that stay in an adolescent ikemen (good-looking person).

As typical with local romantic dramas, the movie is also something of a fantasy, from the heroine’s high end private high school to its story of romance blooming from a phony, terribly awkward start. The story of Cinderella is also a stretch, is it not?

Erika Shinohara (Fumi Nikaido) is a first-year high school student clinging to the edge of the above-mentioned clique, when her new friends begin chatting about their sweethearts– and she lies so as not to be excluded. When they press her for photographic evidence, she goes to Shibuya with her one genuine good friend, the straight-talking Ayumi (Mugi Kadowaki), and snaps a candid shot of an attractive guy. Her clique is suitably pleased and Erika is eliminated, till the image’s subject, Kyoya Sata (Kento Yamazaki), shows up at school– and she begs him to phony a relationship so she does not lose face. He concurs, with the formerly stated condition.

From here, the story might have gone into the familiar territory of adolescent ijime (bullying), which can be found in both dozens of seishun eiga (youth films) and all-too-many paper headings. In reality, Kamiya (Nobuyuki Suzuki), Kyoya’s similarly looks-advantaged friend, proposes the sort of caddish exploitation Erika has actually unwittingly signed up for.

Get the movie here

For her, Kyoya goes out of his way to play his BF function, including a genuine date to give her more photographic evidence for her still-suspicious friends. Relief and gratitude develop into affection– and something more, despite his put-downs and sneers. Even when Erika goes to his roomy house to nurse him through a bout of fever (with mommy and dad nowhere in sight), he keeps up his front of scorn and indifference. This teenaged god, we see, grew up lonely– and discovers it hard to trust anybody, specifically women who think he is excellence on 2 legs.

In a three-decade profession that varies from indie award winners to commercial hits, Hiroki has actually become known for drawing career-peak efficiencies from his lead actresses, while Nikaido is a formidably gifted chameleon who can make any function indelibly her own. With long traveling shots and extended close-ups, Hiroki tests her to the limit and Nikaido increases to the difficulty, exceeding surface comic desperation to raw vulnerability and heart-stricken discomfort. I believed my own memories of teenage love pain were safely buried; Nikaido’s bravura efficiency showed me wrong.

As Kyoya, Yamazaki plays the superior, condescending jerk while exposing enough of the character’s carefully concealed nice-guy side to keep him from ending up being absolutely despicable– a neat balancing technique. Kyoya has to contend with Ryo Yoshizawa’s Kusakabe, a shy, genuine classmate who provides Erika love without the slights, and his older sister Reika (Nanao), a tough-minded beauty who opens Erika’s eyes to particular realities about her brother and the romantic video game.

Will he wake up one day and find the Wolf Girl not at his door?

Get the movie here

Recent Comments